Shipworm

Introduction

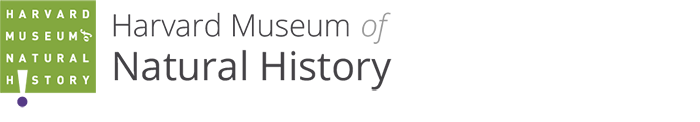

If it looks like a worm, and its name sounds like a worm, is it a worm? The naval shipworm, or Teredo navalis, is not actually a worm at all. This marine mollusk has a very elongated body with a tiny, reduced shell, which covers its anterior end and is often compared to a helmet. It is a bivalve mollusk, meaning two-shelled, like clams and mussels, but unlike other bivalves, shipworms do not need hard shells to shelter their bodies because they bore into pieces of wood, which protect the animals.

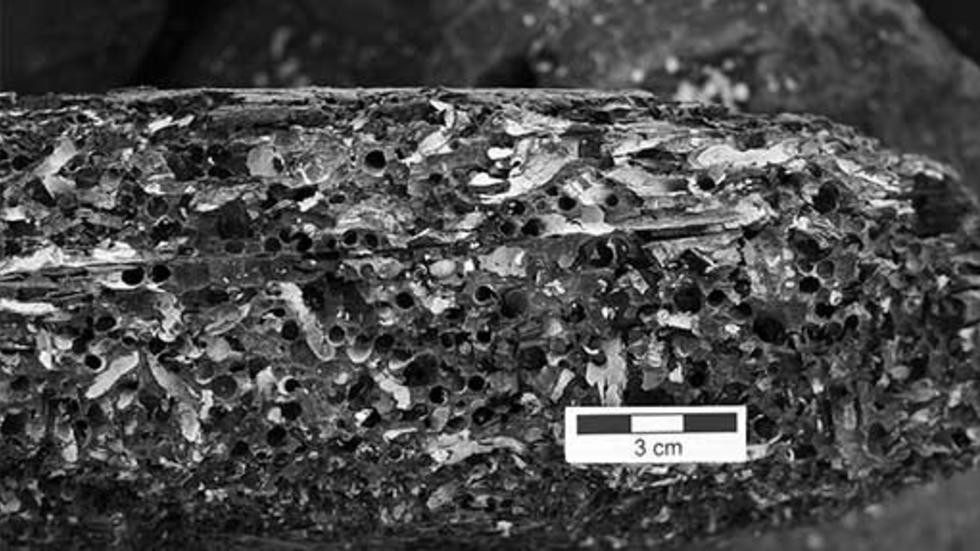

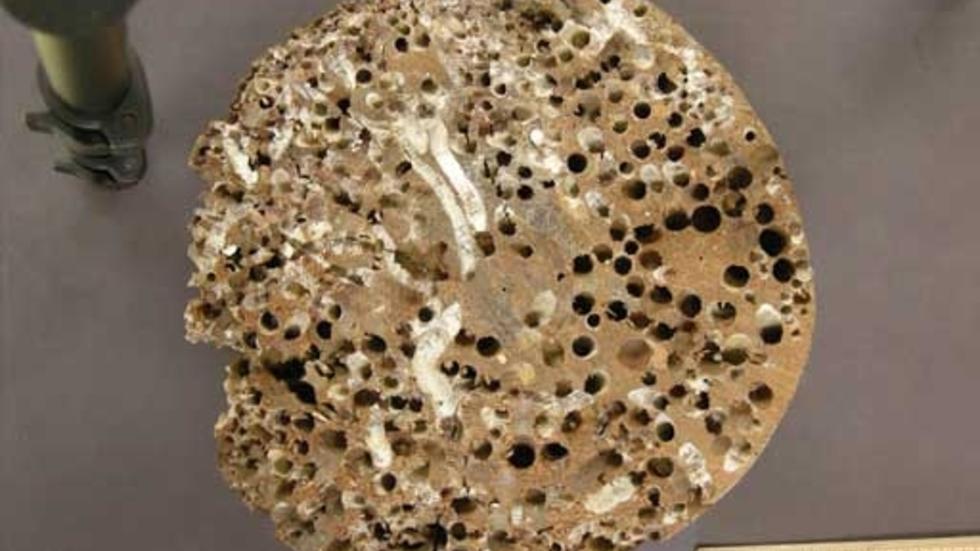

An individual Teredo, removed from its home in a mangrove trunk. Credit: Deplewsk/CC BY-SA 3.0 | The shipworm uses its helmet-like shell to scrape wood particles off the wood surface, which are then moved by cilia to the shipworm’s mouth. They have a symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-consuming bacteria that live within specialized cells in their gills and help digest the cellulose in the wood. They may also filter feed on plankton, in addition to their rigorous woody diet. A single naval shipworm lives to be around three years old, growing to about 25 cm/9.8 inches long. The earliest fossils of wood-boring clams are from the Jurassic Period, some 170 million years ago, although trace fossils showing evidence of wood-boring organisms can be found from a much earlier time. |

The Name

The shipworm’s distinctive morphology gives it a deceiving worm-like appearance, and shipworms were not actually identified as mollusks until 1733 by Gotfren Snellius, a Dutch zoologist. The reason behind “ship” as part of their common name is fairly obvious, as wooden ships are part of their diet, along with other wood that is immersed in seawater. There are many species of shipworm but one of the most widespread is Teredo navalis. The genus name, Teredo, comes originally from a Greek word that means “to rub,” while the species name navalis comes from navis, which is Latin for “ship.”

Termites of the Sea

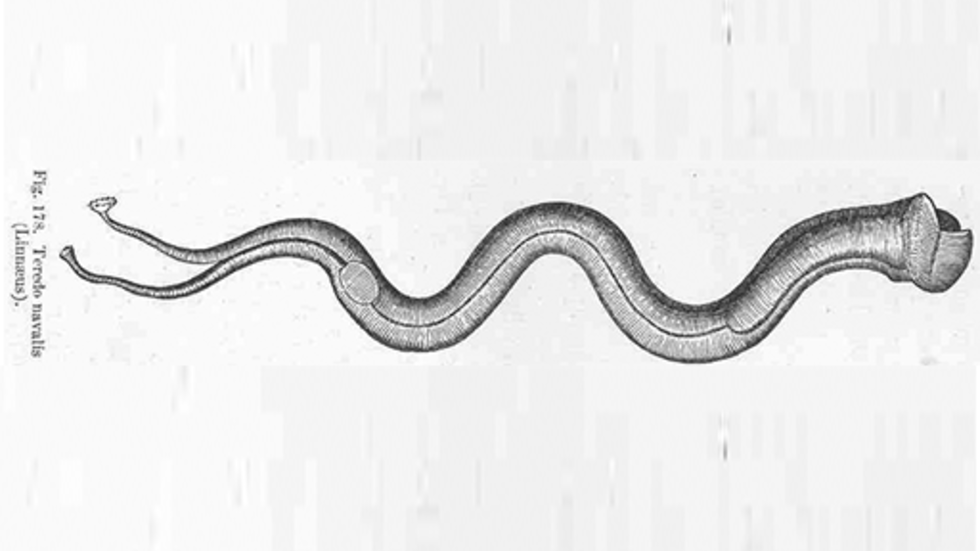

The Barmouth Railway Bridge in Wales has been closed for 20 years because destruction by shipworms has rendered the bridge unsafe. Credit: Trevor Rickard. CC BY-SA 2.0 | This surprisingly tough mollusk has had a significant impact on human history. Since the earliest mariners, ships have sunk as a result of shipworm activity weakening their structure. In 1503, some of the vessels on Columbus’ fourth voyage to the Americas sank due to shipworm damage. In 1731, shipworms did so much damage that they caused floods in the Netherlands when dike gates there became so weak that they failed in strong storms. The introduction of copper sheathing in the eighteenth century slowed the destruction of ships, but in 1919–1921 a succession of wharfs, piers, and ferry slips collapsed in San Francisco Bay following infestation with Teredo navalis, at a cost of hundreds of millions of dollars in today’s prices. Even today, with chemical and other treatments (many of which damage life in nearby ecosystems), the economic cost of shipworm damage amounts to tens of millions of dollars a year.

|

The geographic origin of the naval shipworm is unclear as they have spread around the globe in the hulls of ships. They are most abundant in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Recent DNA work has confirmed that Teredo navalis has spread into the shallow waters of the Baltic Sea, which threatens thousands of archaeologically-important and well-preserved shipwrecks in that area. Teredo navalis is also an invasive species and often outcompetes the native shipworm species in a new ecosystem.

Did you know? More than 3,000 years ago, the ancient Phoenicians and Egyptians covered their boats with pitch and wax to prevent shipworm incursions. The Greeks and Romans used lead, pitch, and tar for the same reason.

Harvard’s "Lady Wormwood"

Ruth Turner Dixon. Credit: Ernst Mayr Library, Harvard University. © President and Fellows of Harvard College | One of the world’s leading twentieth-century experts on shipworms was Ruth Dixon Turner, one of Harvard University’s first tenured women professors, and sometimes called “Lady Wormwood” by fellow researchers. Supported by the Office of Naval Research, Turner spent many decades studying wood-boring mollusks and published more than 100 scientific papers on every aspect of their biology. Her 1966 book, A survey and illustrated catalogue of the Teredinidae was widely acclaimed and provides information that is fundamental to shipworm research today. In particular, she worked on deep-sea wood-boring clams, the xylophagaines, which decompose wood that has fallen to the sea floor. She worked with Robert Ballard, on his discovery of the Titanic in 1985, to identify the shipworms that had caused substantial loss of wood in the wreck. |

Did you know? Shipworms can survive for prolonged periods in anoxic environments, staying in their sealed tunnels and utilizing sugars stored in their bodies.

Did you know? Like so many other invertebrate animals, shipworms have larvae that are different from their adult body plans. Shipworm larvae are called "veligers" and move by swimming using cilia. They measure just 1 mm/0.4 inches in diameter and enter wood by boring tiny holes.

Learn More

Slideshow Image Credits

Teredo navalis by Fibuier, Louis. 1868. Ocean World: Being a Descriptive History of the Sea and its Living Inhabitants. New York: D. Appleton & Co.; Fig. 178 via eshwater and Marine Image Bank, University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections. Public Domain; Driftwood bored by shipworms.by Michael C. Rygel, Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA; Burrows of Teredo navalis by Will Hornbeck via Molluscs - eBivalvia LifeDesk. CC BY-NC.